Family and the Populist Party

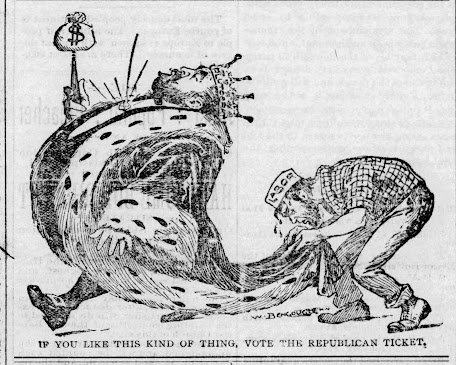

This 1892 political ad, saying, "If you like this kind of thing, vote the Republican ticket," could also have featured a farmer carrying the king's coattails. A constellation of conditions led farmers and laborers to abandon the Republican Party in Kansas -- for awhile.

The Kansas farmer couldn’t seem to get a break. After a steady sweep of good years, in the late 1880s, there was drought. Unlike the old days of subsistence farming, he was beholden to the bank. Greedy railroad barons and elevator operators - or so he saw them - kept freight prices and grain storage costs sky-high. His success in producing boast-worthy crop yields became a liability. Commodity prices tumbled, and kept dropping. Legislation just seemed to favor the rich. Indeed, what was worse was that it was all a conspiracy, a deliberate plot to keep the farmer down, or so many said. Who cared about the farmer?

From 1889 at least through 1913, members of my grandmother’s family were part of a radical political movement in Kansas. It was Populism, in which small farmers, the “little guys” rose up challenging banks, railroads, big corporations and other monied interests.

Kansas, a bedrock of conservatism today, was briefly the epicenter of this movement that pushed to dramatically change American society. Lucius T. Barbour, my Grandma’s great-uncle; her mother’s cousins Andrew and Bruce Patchett, and John Dilling Harkins, a cousin’s husband, were elected to, or ran for positions within the framework.

It was also called the People’s Party. In 1892 the party rose to power in Kansas, electing a Populist governor, gaining control of the Kansas House of Representative and sending a Populist senator to Washington. The senator was William A. Peffer, familiar to the Barbours, Patchetts and Harkins as editor of the Coffeyville Weekly Journal.

Here is an example of the warnings farmers received, from the editor of a Lawrence newspaper in 1890:

"If it is a fact that the farmer is not in full enjoyment of his rights, and that other classes are combined to deprive him of the fruits of his own labor, it is evident that organization among farmers is an absolute necessity. Those who have read these columns for the last thirteen years have full knowledge of the details of the various capitalistic conspiracies against the interests of agriculture. Railroad, tax, patent, food-adulterating and trust-robberies in all their different phases have been exposed, the conspirators held up to contempt, and the farmers have been urged to mass their strength and efforts against the systematic efforts to rob them and deprive them of their rights and, in some measure, their liberties...

Indeed, but for the ceaseless, determined and emphatic opposition to the schemes and plots of the financial plunderer of the farmers, the trusts and monopolies in general would to-day be masters of the situation and the people on farms would be hopelessly bound in chains."

In 1889, Lucius was elected head of the Farmers’ Alliance, a precursor to the Populist Party, in Sandy Ridge, Fawn Creek Township. In 1896, Bruce was chosen as a delegate to the Montgomery County Populist Party Convention. In 1897 Bruce ran for the Coffeyville School Board on the related Citizen’s Party ticket. In 1904, Andy and John Dilling Harkins ran for constable in Fawn Creek Township on the Socialist Party ticket, and John’s brother George Harkins ran for justice of the peace. In 1913 Bruce Patchett was chosen as delegate to the Montgomery County Populist Party convention.

What was it about this movement that appealed to these men? What kinds of specific conditions led to a third party rising to power?

A look at the Populist Party platform at their first national convention in 1892 does not look unfamiliar today. The party called for government ownership of railroads, telegraph and telephone companies; government loans for farmers, banks established with the government guaranteeing deposits; the election of senators by popular vote, a graduated income tax, a secret ballot, an eight-hour workday, and opposition to any subsidies or national aid to private business. The party also supported women’s suffrage. Then too, their official platform called for the prohibition of land ownership by foreigners, and restriction of immigration by paupers and “undesirables.” A good part of the platform came true decades later. Other issues, such as immigration, are still discussed periodically, both condemned and praised.

A Cluster of Conditions

At the risk of sounding like a textbook, here is some background:

The years 1880-1885 in Kansas were years of unusual growth and prosperity. The population of the state rose from 90,000 to 1,200,000 while the value of property doubled. They were years of unusually high rainfall and high crop yields. High wheat and corn prices resulted. In some parts of the state good land was still so cheap that it was possible to pay for the land from the products of a single year. Of course this led to land speculation creating a fictitious demand and inflating prices.(1)

Accompanying the boom was excessive building of railroads. The railroad companies built miles of track with grants of land, and money grants from the state, federal and local government - even from individuals. In effect, promoters could build with little expense or risk to themselves. The purpose of the roads was not to carry traffic but to increase land value. In 1885-86 enthusiastic municipalities voted for $10,000,000 in bonds for the railroad. Every tiny town hoped theirs would be a new Chicago, and everyone who got in at the beginning would be rich.(2)

The collapse of this boom came in the winter of 1887-88 when there was a sharp drop in prices for agricultural products. Corn prices dropped from 83 cents a bushel in 1881 to 28 cents in 1890.(3) (Its 1870 price was 48 cents a bushel.) The large corn crop in 1889 sold for 10 cents a bushel.

Eastern Kansas was Republican by tradition, and opposition was considered incomprehensible and downright treasonous.(4) But by the late 1880s the emerging economic crisis threatened to undermine the GOP’s claim as the party of prosperity. Many farmers feared losing their land and becoming tenant farmers. They began to believe that too much legislation favored the wealthy while neglecting or taking advantage of the working class and the farmer. They especially resented the railroad companies for high freight rates that cut into profits, and bankers for high interest as there was increasing need to borrow for farm machinery and seed. Two distinct organizations were birthed from this: The Farmers’ Alliance and United Labor Party.

The Farmers’ Alliance responded by trying to set up cooperatives to have more control over buying supplies and marketing products. The group was officially politically neutral, though.

In 1887 the United Labor Party paid to distribute 50,000 copies of a book, Seven Financial Conspiracies Which Have Enslaved the American People, by Sarah Emery. From 1887 to 1896, another 400,000 copies were printed. Emery said the American worker had been subject to a life of “unremitting, half-requited toil.” According to her, the “money kings of Wall Street” obtained control of the nation’s finances after the Civil War, a conspiracy accomplished by the passage of seven pieces of legislation passed from 1862-1879. The national banking system, for example, was “deliberately planned for the purpose of robbing the people.” The British were behind this conspiracy. A rise in foreclosures was seen as a plot by foreign capitalists.

In 1890 the Farmers’ Alliance called for a system that would reduce mortgages on farmland as the land fell in value, with no taxes on homesteads. This would require a legislative solution, however. Many members turned to the Populist Party.

William Peffer, the Coffeyville newspaper editor turned Populist senator, edited a Topeka-based populist newspaper, the Kansas Farmer. He was the only prominent Kansas populist who did not go along with the conspiracy theories, according to one historian, but he did give Mrs. Emery’s views a lot of attention in his paper.(5)

Picnics and Songs

As with any occasion where people in the nineteenth century gathered, there was poetry, oratory and song. Picnics and rallies even in small towns began to draw over 1,000 people and 200 or more wagons. The Quenemo Glee Club, a mother-and-children quartette, was very popular at People’s Party rallies. They created a songbook full of Populist lyrics. Here’s an example of one of their most popular numbers:

Labor In Want

Can you give any reason how it came about

That my children are dy-in for bread?

When I’ve worked all my life and am nearly

Played out,

Tryin’ hard to get something ahead?

There is some folks I know of that hain’t done

A tap,

And they ride in their carriage and four

And have got so much wealth they don’t know where

They’re at,

While the toiler is ragged and poor.

When they foreclosed the mortgage and

Took the old home,

It was sad to lay mother away,

And I couldn’t keep from thinking of what

Would become

Of poor Bessie and Bennie and May,

For I’m getting old now and my work’s

Nearly done,

Upon whom will my darlin’s depend?

Without clothes, without food, without friends

Or a home,

Will the millionaires care for them then?

Bruce and Andrew Patchett were the sons of a homesteader. By the time they were adults, land in Montgomery County was expensive; starting their own farm the way their father did was no longer an option. Lucius’ farm was purchased for him by his father, and his father retained ownership. It was an investment. But Lucius had to make a go of it. There are a number of reasons one can imagine for their interest in the Farmers’ Alliance and People’s Party.

A Brief Moment in the Sun

The Populist Party's rise was swift, dramatic – and fleeting. In 1896 William Jennings Bryan presented the party with a choice. A Democrat, he seemed to offer exactly what the populists wanted. Should members throw their weight behind him or seek someone else, returning to a two-party system? The Populist Party nominated Bryan for president, and many members followed him into the Democratic Party.

The Patchetts remained active in causes dear to the People’s Party even after its demise, transferring their allegiance to the Citizen’s Party and the newly-formed (in 1901) Socialist Party. Lucius Barbour, however, had never dropped his loyalty to the Republican Party, and in fact, proudly named his last son McKinley in 1895.

Notes:

Miller.

Miller.

Argersinger.

Miller.

Ostler, “Rhetoric of Conspiracy.”

Sources:

Newspapers:

Lucius elected: Coffeyville Weekly Journal, 20 Dec 1889, p. 3.

"Alliance and Grange Organization. The Necessity For Organization Among Farmers Is Apparent," The Jeffersonian Gazette (Lawrence, Kansas), 3 July 1890, p. 3.

“Great Rallies - That Quenemo Glee Club Pleases.” The Topeka Daily Press, 28 July 1894, p. 1.

“Scott At Key West,” Burlington Courier (Burlington, Kansas), 14 Sept 1894, p. 1.

“Populist Primaries,” Coffeyville Daily Journal, 12 Mar 1896, p. 2.

“Here They Are, Make Your Choice,” Coffeyville Daily Journal, 27 Mar 1897, p. 1.

Andrew on Ballot as Constable: South Kansas Tribune (Independence, Kansas), 18 Nov 1904, p. 1.

“Township Officers,” Coffeyville Daily Journal, 22 Nov 1904, p. 3.

Bruce chosen as delegate: Coffeyville Daily Journal, 6 June 1913, p. 4.

Other:

Argersinger, Peter H. “Road to a Republican Waterloo: The Farmers’ Alliance and the Election of 1890 in Kansas,” Kansas History, A Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 33 No. 4 (Winter 1967), pp. 443-469.

Emery, Mrs. Sarah E.V. Seven Financial Conspiracies Which Have Enslaved the American People,” Lansing, Michigan: Robert Smith & Co., 1894.

“125 Years of Farmland Values in Kansas 1870-1997,” Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service, https://agribusiness.purdue.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/r-9-2001-tsoodle-wilson.pdf

Miller, Raymond Curtis. “The Background of Populism in Kansas,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 11, No. 4 (March 1925), pp. 469-489.

Ostler, Jeffrey. “Why the Populist Party Was Strong in Kansas and Nebraska But Weak in Iowa,” Western Historical Quarterly, Vol. 23 No. 4 (Nov. 1992), pp. 451-474.

Ostler, Jeffrey. “The Rhetoric of Conspiracy and the Formation of Kansas Populism,” Agricultural History, Vol. 69, No. 1, (Winter 1995), p. 1-27.

Peffer, William A. “The Mission of the Populist Party,” 31 Dec 1893, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/the-mission-of-the-populist-party/

Quenemo Glee Club, in the People's Party Campaign, 4th Congressional District. "Truth Against the World Campaign Songs," Kansas Memory, Kansas Historical Society, https://www.kansasmemory.org/item/203950/page/1

Comments

Post a Comment