October Gleanings From Fort Wayne, Indiana: Grave Robbing, The First Telephones and Buffalo Bill

Usually I gather “Gleanings” from the Coffeyville, Kansas newspapers from the 1870s through 1890s. This time I went through Fort Wayne, Indiana newspapers from the same time period. I had ancestors in both places.

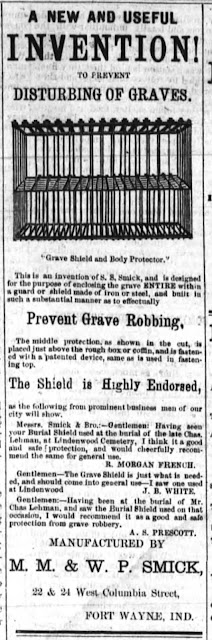

An ad for a grave shield ran in the Fort Wayne Daily Gazette on 13 Feb 1879, reflecting national fears of grave robbing.4 Oct 1879 Fort Wayne Daily News

The Fort Wayne Medical College, under the new law, have provided themselves with at least one cadaver. It was taken from the poor house graveyard a few days ago. His name was Smith.

Olds’ Spoke Factory and sawmill are being connected by telephone.

- Hickory nuts are plentiful this year.

Grave-robbing or body-snatching was a problem that arose as medical training advanced. Simply put, demand outstripped supply. People tended to look the other way when the bodies came from the Black population, the imprisoned and the poor. But when “decent” members of society were dug up, that got a strong reaction. There were those who believed all along, of course, that no corpse should be dug up without permission.

“Every man’s grave is sacred, and the ghoul who desecrates the grave of a pauper should receive as severe a punishment as the one who robs the grave of the wealthy,” the editor of the Waterloo, Indiana paper wrote after a local man’s body was dug up and sent to Fort Wayne in January 1879. “The public safety demands that this wholesale grave-robbing business be stopped and the sacred contents of the grave be respected.”

In March 1879 Indiana passed its first so-called anatomy law. Under this law, medical schools had to keep records on all of the cadavers used. Bodies that had not been claimed within 24 hours from state and local institutions such as prisons, jails, asylums or public hospitals could be used for dissection. All other corpses were to be off limits. (See my blog post, “A Victorian's Worst Fears, Part II,” for more on this issue, particularly why the poor strongly feared dying a pauper.)

So under the new law, the Fort Wayne Medical College acted properly in digging up poor Mr. Smith. As to the grave shield, an earlier version known as the "mortsafe" appeared in England around 1816. Something only the wealthy could afford, they resembled cages that were placed atop the grave site.

The announcement that telephones were connecting two businesses in October 1879 seems impressive at first. After all, the state’s first telephone company organized in December 1878, and by March 1879 the state’s first telephone exchange was up and running in Indianapolis.

But the Olds’ Spoke Factory and Sawmill weren’t the first in Fort Wayne to get telephones. This technology spread fast. In June a Mr. Sid C. Lumbard labored to establish a telephone exchange in the city, writing the Fort Wayne Sentinel with details. After examining the merits of the Bell telephone and the Edison telephone, he decided to go with the former. He expected the equipment he needed - a switch board, batteries, call bells, etc. - to arrive on the 15th and was negotiating for the purchase of poles and wires. He expected the latter to be installed and to be in operation by mid-July. He reported having thirty subscribers already. The cost was $30 to $60 per year. That was an outlay for the customer of about $915 to $1,830 a year in today’s dollar value.

By July 21 the Fort Wayne Sentinel reported that the telephone was a “constant source of wonder and marvel to all.” How astonishing it was, for example, that Dr. Myers was able to successfully call in a prescription from the city hospital to Meyers Brothers Drug Store and get it promptly filled, or that two people at opposite ends of town could converse as if they were in the same room.

There were certainly also frivolous uses for this novelty. The Fort Wayne newspaper editor spent an hour at the Edison Telephone Exchange office with “chief cook and bottle washer” Orin Perry, as he connected calls. He would answer with, “Halloa, what do you want?” Most people, of course, wanted to be connected, but one person requested a song.

“Of course,” Perry replied, and in a “beautiful tenor” he sang:

She’s a darling,

She’s a daisy,

She’s a dumpling

She’s a lamb,

You should hear her play on the piana,

Such an education has my Mary Ann.(1)

Another caller requested a song, and Perry obliged with a humorous song about boardinghouse hard-boiled eggs. Soon after, Mike Welch, clerk at the Aveline Hotel, called to ask Perry, “What’s the difference between you and a jackass?” Perry answered, “Only half a square!”

By the end of July, Sid Lumbard’s operator connected subscribers so they could be entertained with a ‘phone concert’ that featured Mrs. Lumbard singing and a piano solo by Miss Nellie Angell. The competing Western Union Telephone Company also had 32 subscribers on their exchange, and connected them all for “an entertainment,” though the newspaper editor said he did not get to hear it since he was not on that exchange.

8 Oct 1879

Apples are plenty.

Buffalo Bill on the 18th.

The state fair has closed.

And still they go nutting.

Another divorce case has been filed.

The Home For the Friendless has seven inmates.

Buckwheat is being thrashed and buckwheat cakes will soon be hashed.

The Fort Wayne newspaper devoted half a page to a preview of his show, accompanied by an ad. The show featured its own brass band and 20 “real Indians,” members of the Ponca and Pawnee, “direct from Indian Territory.” There was Buttermilk the trained donkey, and of course, the hero himself. Buffalo Bill starred in a play, “Knight of the Plains,” performed a rifle shooting demonstration, firing the gun from “every conceivable position,” and staged the “most realistic” tableaux of a prairie fire “ever produced on stage.”

Buffalo Bill’s “orchestra and military band” led a parade through the town daily before performances.

Critics were pretty breathless about the show and declared his acting skills to be “much improved.” At a time when increasing numbers of men had white collar jobs and there were concerns about men becoming “too soft,” Buffalo Bill was held up as a paragon of manhood. Reserved seats were 75 cents, nearly $23 in today’s value. Ladies were assured - or maybe it was their husbands who were being assured on their behalf - that the show was not too “rough.”

The show was sold out in Fort Wayne and played to a standing-room-only crowd.

The Home for Friendless Women and Children was begun in 1873 at the corner of Pine and Locust Streets. This type of asylum was established first in eastern cities in the 1840s and spread west. They were a more desirable alternative to the dreaded poorhouse, where residents were judged to be there through their own moral failings. At the poorhouse one might be housed with “lunatics,” alcoholics, cognitively and physically challenged individuals, the blind, and senile elderly. Many Homes for the Friendless sprang up after the Civil War. Sometimes, they were exclusively for “fallen women.”

These institutions lasted, in varying forms, even into the 1980s (although renamed). A 1914 report at a Sagamon County, Illinois Home gives a glimpse into the horrifying conditions so many women were forced into if they did not have a man to support them:

“Mrs. A.” was forced to support herself and her children as she was divorced. Her husband was ordered to pay child support but failed to do so. He’d been arrested twice for this failure. She placed her children, a six-week old baby and a four-year old, at the Home for the Friendless, paying $10 a month for their care. Three weeks after having the baby, and three weeks before placing her kids, Mrs. A. had a surgical operation. Yet she took a position as a dishwasher at a restaurant, working from 6:30 in the morning till 8:00 at night, seven days a week for $5 a week plus meals. She was standing all day, lifting trays of dishes weighing 50 to 75 pounds and at times thought she’d faint in the hot, steamy room. She was transferred to potato peeling. She could not get ahead because she had to pay for her children’s care and for her own accommodations.

The Fort Wayne Home for the Friendless was opened as a home for “fallen” women. Prayer meetings were held at 3 p.m. on Wednesday afternoons.

16 Oct 1879

Mr. Charley Burnett has gone to Chicago to see the elephant.

The National Christian Temperance Union will hold their convention in this city beginning on Nov. 7th. The convention will be held at Second Presbyterian.

Squirrel pot pie is ripe.

Old John, the old fire horse, who has done service for the last thirteen years, is now lamed up and incapable of performing duty.

Ruth Trease is evidently a bad woman. An affidavit is on file in Justice Beek’s office, wherein she acknowledges the crime of adultery charges against her by her husband, Daniel Trease. She admits the charge.

Seeing the elephant was an extremely common expression that meant seeing something exciting and long-anticipated, but at great cost. Soldiers used it during the Civil War, and in many circles it meant experiencing combat. It was also a frequent expression for pioneers on the overland trails.

There were good reasons temperance crusades were such an issue in nineteenth-century America as alcoholism rates were much higher than today, and women were almost entirely financially dependent on men. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union is the best-remembered of the national temperance groups today. The National Christian Temperance Union was headed by Francis Murphy, an Irish immigrant and reformed alcoholic who was headquartered in Pittsburgh. He became famous for the “Murphy pledge:”

With malice toward none, with charity toward all, I hereby pledge my sacred honor that with God helping me, I will abstain from the use of all intoxicating liquors as a beverage, and that I will encourage others to abstain.

Everyone in America knew what it meant if they heard, “Have you signed the pledge?” At the time Murphy spoke in Fort Wayne, the pledge was only three years old. The first year, an estimated 65,000 to 80,000 people signed the pledge. They received a card with a blue ribbon, and people began wearing blue ribbons. By the time Murphy died in 1907, millions had signed the pledge, including my mother’s paternal side of the family.

Although named a national organization, the Fort Wayne convention had delegates only from Indiana, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, Kansas, New York, and Missouri. My third great-grandfather, Myron Fitch Barbour, was involved in temperance groups and may have attended this convention, although he was not a delegate. In the late 1860s he was president of the board of Second Presbyterian Church, which hosted the event. The convention lasted four days.

23 Oct 1879 Fort Wayne Daily News

Telephones are going up everyday.

Carpet rag parties are all the rage.

Peanut stands are springing up on every corner.

Typhoid fever seems to be the prevalent complaint.

Calhoun street was today crowded with wagons loaded with grain and potatoes.

There are different ways to make rag carpets. One is cutting wool into strips and using a rug hooking tool to hook them into a burlap-like backing. Another is sewing strips of fabric rags together, braiding them, and coiling the braids into an oval or circle, hand-sewing them together. My grandmother made several of this kind during the Depression that she still had on her floors fifty years later. A third method was sewing the strips together and weaving them into small rugs. These were almost always sent out to a weaver. A fourth method involved crocheting the strips of fabric.

The articles on rag carpet parties did not specify which method would be used, but the participants were sorting fabric from old clothing, sheets, tablecloths, etc., cutting them into strips, sewing the ends together and rolling them into one-pound balls. It took at least one pound to yield one yard of rug. Such tedious work was definitely made more bearable with a bunch of friends.

Rag carpet making seemed to go through a series of waves in popularity. In 1883 Edgar “Bill” Nye, a nationally-known popular humor writer, joked that “lady friends are looking with avaricious and covetous eyes at my spring suit,” in anticipation of cutting it up for a rag carpet.

From the late 1890s and early 1900s there were stories from time to time about rag carpet revivals. A 1901 article in a Vermont newspaper said that, “Instead of burning or selling their old rags the women are now saving all they can lay their hands on, and it is no uncommon thing to be greeted by the request: “Won’t you please save all your scraps and pieces for my rugs?” It is said the men who ply the lucrative trade of collecting rags are disgusted at the dearth of the once plentiful material…”

The carpet rag parties often seemed to involve 20 to 30 women and sometimes men, who wound the strips of fabric into balls. It was a large number of people in what were mostly small houses, and with a chicken dinner to prepare for a crowd.

There were so many terrifying diseases that our ancestors had to contend with. I’ve thought about what Laura Taylor Suttenfield, my fourth great-grandmother, dodged to live to be 91. Typhoid fever is life-threatening and spread by bacteria in contaminated food and water. According to the World Health Organization, even today an estimated nine million people worldwide contract typhoid fever, and 110,000 die of it each year. Other sources, such as the Wisconsin Division of Public Health, peg the number of cases worldwide at 12.5 million. It is common in places with poor sanitation and a lack of clean drinking water. In the United States today, there are about 400 cases per year, about 70 percent of which were acquired during international travel.

Notes:

1. "She's a Daisy (She's a Darling, She's a Dumpling, She's a Lamb)," written by J.F. McArdle, was a huge hit. Popularized by the comedian J.G. Taylor, the sheet music was published for the parlor in 1881.

Sources:

Beckley, Lindsey. “King of Ghouls” Rufus Cantrell and Grave-robbing in Indianapolis,” 31 Oct 2020, https://blog.history.in.gov/2020/10/

Home For the Friendless,” History of Sagamon, Illinois, Sagamon County Historical Society, 30 Oct 2013, https://sangamoncountyhistory.org/wp/?p=2420

“Indiana Bell 1877-1984,” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, https://indyencyclopedia.org/

Nuland, Sherwin B. "The Uncertain Art: Grave Robbing," The American Scholar, Vol. 70, No. 2 (Spring 2001), pp. 125-128.

Newspapers:

“Home of the Friendless,” The Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, 2 Nov 1873, p. 1.

“It Has Struck Waterloo! The Grave Robbing Mania! The Grave of James Little Empty!” Waterloo Press (Waterloo, Indiana), 23 Jan 1879, p. 3.

“Legislative Summary,” The Monticello Herald (Monticello, Indiana), 20 March 1879, p. 4.

“A Telephone Exchange,” Fort Wayne Sentinel, 4 June 1879, p. 4.

“Telephonic Talk. An Hour at One of the Exchanges. The Modus Operandi of Making Connections. Mirth and Music Over the Wires,” Fort Wayne Sentinel, 21 July 1879, p. 4.

“T.T.T.T. Which is Latin for Taffy Through the Telephone. Pleasing Effects and Startling Calamities All to Be Laid to the Telephone,” Fort Wayne Sentinel, 28 July 1879, p. 3.

“Hon. W.F. Cody (Buffalo Bill),” Fort Wayne Daily Gazette, 17 Oct 1879, p. 1.

“Rag Carpets (From the Boston Journal),” Rutland Daily Herald (Rutland, Vermont), 12 Sept 1896, p. 2.

“Revival of Rugs of Rags,” St. Johnsbury Caledonian (St. Johnsbury, Vermont), 27 March 1901, p. 4.

Copyright by Andrea Auclair © 2023

Comments

Post a Comment