Chicago's Fisher Building and Its Barbour Connection

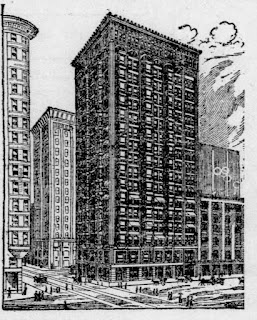

The Fisher Building at 343 Dearborn Street in Chicago

Go big or go home. If that saying existed in 1895, it applied to Lucius George Fisher II. Lucius built a skyscraper at 343 Dearborn in the Chicago Loop that was spectacular for its time - a “world beater,” in the slang of the day. When it was completed, it was one of the tallest buildings in the world. Today, it is Chicago’s oldest standing skyscraper, as its peers gradually fell to the wrecking ball.

As with any new skyscraper even today, it was described in superlatives. Everything about it was the biggest, most, best, according to the Chicago press.

In June 1895, when Lucius, a real estate developer and paper-making magnate, secured a loan for half a million dollars, it was said to be the largest ever placed in Chicago on leasehold property.

Only ten months passed from the time a building contract was signed to the time tenants moved in.

At the time it was built, it was the tallest building erected in Chicago under one contract. (The Masonic Temple Building was taller but had several builders.) The Chicago City Council had been working to limit the height of office buildings to 12 stories. However, Lucius was granted a building permit before this took effect, so he was allowed to build a tower of 18 stories. Later, two more stories were added.

The construction cost was $1,250,000.

The interior was said to be the most expensive in the country. It had six elevator banks, each elevator with ornate cages. The first two floors were covered in mosaics, and the lobby was onyx and bronze with Carrara marble ceilings and staircases. Each office had mahogany walls and a marble wash basin with a plate glass mirror.

In May 1896 architects were hired to design the bar and buffet; they were decorated with San Domingo mahogany, onyx and gold plate at a cost of $25,000.

Enthusiastic writers said that Fisher, through the design team of D.H. Burnham & Company, introduced more innovations to office dwellers than anyone else. A wash basin in each office was apparently a big deal. But imagine – chilled water in each office! Anyone who has spent time in downtown Chicago on an August day can appreciate this - especially anyone old enough to have memories of un-air conditioned buildings. A few office buildings “made an effort to furnish ice water in the corridors at a fountain where Tom, Dick and Harry quenched their thirst,” a newspaper reporter wrote. But at the Fisher building, each office had its own continuous supply piped in, chilled to 33 to 38 degrees.

Another technological marvel that writers gushed over was the pneumatic clock system in the Fisher building. “One of the most interesting inventions in recent years….undoubtedly the greatest device ever contrived” for keeping an entire building’s clocks accurate, the Chicago Tribune said. There was one master clock on the eighteenth floor, a ten-foot-tall clock that “runs by pendulum and weights in the usual manner.” All the other clocks in the building lacked clockworks; they were operated by compressed air. In March 1896 the Tribune reporter said this marvel was available for a small fee, but an October article in the same paper said it was included in the price of rental, just as janitorial services were.

The "wonder clock" and “filtered ice water” in each office were prominently mentioned in an April advertisement for tenants.

The first floor featured ten stores; it also had two bathrooms. The second floor housed a bank, with the vault in the basement.

The building is described as neo-Gothic today, but newspapers at the time called it French Gothic. Its exterior was (and is) an orangish, semi-glazed terra cotta. It was decorated with fanciful figures such as eagles and mythological figures on the upper floors and fish, crabs, shells and other aquatic creatures on the lower floors, in a play on the owner’s name.

The building was a financial success and had early tenants like the Otis Elevator Company, which made skyscrapers possible, and the national board of the Knights of Pythias. Lucius of course moved his own company’s headquarters to his modern wonder, too. He resigned as company president in 1909 but remained chairman of the board.

Lucius George Fisher II

In 1861 he moved to New York where he clerked in a hardware store. When the Civil War broke out, he joined the 84th Regiment of the New York Infantry. His parents moved to Chicago, where his father began working in real estate and real estate investment. The young Lucius joined them there after the war. He began working for the Rock River Paper Company, its owner an old friend of his father’s. Lucius advanced rapidly with the company and eventually incorporated his own, the Union Bag and Paper Company, in the 1870s. It became the leading paper bag manufacturer in the United States and also produced other products such as a patented “pressed-paper plate for grocers’ use.” Like his father, Lucius invested in real estate.

His father died a wealthy man, a millionaire, but Lucius II surpassed him. He and his wife Katherine lived a life likened to the fictional Crawleys of “Downton’s Abbey.” One of his real estate investments was a 160-acre tract on the Southside of Chicago. The grounds for the Chicago World’s Fair happened to be mapped out right next to this tract. His property suddenly became worth about $266 million dollars (in today’s value). He leased the land and 600 three-story houses were built upon it for visitor accommodations.

Later, he commissioned the World’s Fair architect, Daniel H. Burnham, to design his skyscraper. (He also purchased a collection of Greek sculpture displayed at the World’s Fair and gave it to Beloit College in 1894 on the college’s fiftieth anniversary.)

In 1885, Lucius and Katherine lived in a newly-built red brick Victorian in the Oakland neighborhood. It was fashionable, with stained glass windows and a ballroom on the third floor. But by the turn of the century, the neighborhood was no longer regarded as so desirable. In another part of town, the president of First National Bank retired and put his mansion, known simply as the Nickerson mansion, up for sale. Built in 1883, it was said to be the most expensive and luxurious house of its day. It had three stories with accommodations for up to 11 servants. The Fishers would have up to six living with them.

Lucius purchased the mansion in 1900 for over $2 million (in today’s value) and hired an architect for some redesign work. He and Katherine enjoyed hobnobbing with their wealthy peers and having events there with their daughters. At their previous, smaller home they once hosted 800 guests in one evening. They also owned a “cottage” on Mackinac Island.

In 1910 Lucius and Katherine were on a European trip, taking the waters in Carlsbad, to be specific, when Katherine died suddenly. Lucius lived in the house until his death in 1916. It remained a private residence a while longer. His youngest daughter, Katherine, lived there with her husband, seven children, and their twelve servants in the early 1920s. Today the mansion houses the Driehaus Museum.

The Fisher Building Today

One by one the wrecking ball and demolition crew came for the Fisher Building’s “friends and neighbors,” until it was the “last man standing” from its era. It was designated a Chicago landmark in 1978. It was converted to a residential building in 2000. Apartments are on the third through twentieth floor, with offices and stores on the first two.

Note: My great-great-great grandfather, Myron Fitch Barbour, and Lucius George Fisher, Sr. were first cousins. So Lucius II is Myron’s cousin’s son. He is also actress Jodie Foster’s great-great-great-grandfather. Read my blog post “West to Wisconsin: A Sketch of Jodie Foster’s Third Great-Grandfather,” for more information on the senior Lucius George Fisher.

Sources:

Newspapers:

“Recent Sales of Real Estate,” Chicago Tribune, 23 June 1895, p. 31.

“Wonderful Clock Invention. New Device That Will Revolutionize the Making of Stationary Timepieces,” Chicago Tribune, 29 March 1896, p. 7.

“New Ice-Water Supply. Device by Which Every Office is Furnished With Cold Aqua-Pura,” Chicago Tribune, 5 April 1896, p. 10.

“Week’s Record in Realty,” Chicago Chronicle, 3 May 1896, p. 28.

“It Has But One Clock. New Fisher Building Tells Time In An Unusual Way,” Chicago Tribune, 25 Oct 1896, p. 47.

“Tries to Leap to Death. Aged Mrs. Margaret May Attempts to Jump Into River,” Chicago Chronicle, 24 Nov 1896, p. 1.

“Bag Directors Chosen,” Chicago Tribune, 7 March 1899, p. 9.

“Elevator Drops, Eleven Are Hurt. Passenger Car in Fisher Building Falls Four Stories, Badly Injuring Its Occupants,” Chicago Tribune, 23 Sept 1900, p. 1.

“Wants $25,000 For Injuries,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), 11 Dec 1900, p. 5.

“Fisher to Build Addition. His Block on Dearborn Street to be Enlarged,” Chicago Tribune, 24 May 1905.

“Lucius G. Fisher Is Dead,” Chicago Tribune, 21 March 1916, p. 15.

Other:

“The Story of the Fishers,” Driehaus Museum, 30 March 2016, https://driehausmuseum.org/blog/view/the-story-of-the-fishers

Comments

Post a Comment