The Eight Sons of Milo Roswell Barber

They were Charles and Myron, Milo Jr. and Calvin, and Sylvester, George, Edwin and Theron. The eight sons of Milo Roswell Barber and wife Miranda Orilla Butler were born over a span of 24 years, from 1833 to 1857. There were two sisters, too; Abi, the oldest child, and Sophronia, increasing the span to 26 years.

Of course, in their era, a large family like theirs wasn’t unusual at all. One could say they were ordinary people, average, perhaps. But what is an ordinary life? Our lives are shaped by the place and time we live in, and national events can have life-changing effects. Six of the brothers served in the Civil War. That was an extraordinary event, of course, and it profoundly marked the lives of each one. It wasn’t common for one family to have six sons serve, and all came back alive. Six sons were also pioneers. That too was a unique event in American history. One other son was knifed to death; one lived nearly the last twenty years of his life in a mental institution. So again, we can ask, what is an ordinary life?

Their Father

Their father, Milo Roswell Barber, was a colorful character who seemed to see himself - and his family saw him - as an archtype. The rugged individual blazing a path through the wilderness - onward pioneer! Wrestling a living for his family with only a gun and ax….single-handedly taming that wilderness, to be rewarded with a well-run farm and neat farmhouse. Everything larger than life: he had 18 children! Three sets of twins! (Though only ten children’s births and names were recorded.) His life spanned the century….so did his siblings’ lives...more bragging rights about Barber/Barbour longevity. And even well into old age, they were hale and hearty; he was still walking into town in his 80s. He did indeed lead a long and remarkable life.

Milo was born in Massachusetts, raised in his parents’ hometown of Simsbury, Connecticut until he was eight, and then had the adventure of moving with a colony of his parents and several aunts, uncles, cousins and neighbors to the Holland Purchase, a huge swath of land in Western New York being sold by Dutch investors. His family group was among the first to arrive and purchase plots in the fledgling town of Sheldon in Genesee County. There, his father Roswell farmed - so did Milo - and his parents were among the founders of the Sheldon Congregational Church.

As an 18-year old, Milo was apprenticed to learn the tanner’s trade back in Connecticut. Most likely he was in Simsbury, and the master tanner was a relative or trusted family friend. Milo practiced the tanning trade in New Jersey for several years, then moved to Greene County, New York. He married Miranda Butler there in 1830, and they had their first four children in Greene County. They came to Indiana in 1838 via the Erie Canal to Peru, Indiana, then by ox team to Kosciusko County where his sister Nancy and her husband Richard Adams lived.

There were the quintessential log cabin pioneer years. A biography published in a local history book said he arrived in Kosciusko County without a dollar. They lived with the Adamses and Milo hunted, trapped and split logs. After a year he borrowed $100 and bought 80 acres. He had the arduous task of clearing the forest before he could plant crops, and build his own log cabin.

By the 1860s, he was a respected older citizen who was appointed the first Seward Township trustee. They were part of the little town of Silver Lake. The log cabin was replaced with a two-story frame house, and his children were going out on their own – and joining this terrible war.

Milo was destined to live a long life. But he wouldn't have many of his children and grandchildren gathered around him in his old age.

War Years

Having six sons serve in the Union Army was a point of pride for Milo. The war's official start date is April 12, 1861 when Confederates fired on Fort Sumter in South Carolina, and three of his sons responded early.

Myron Francis Barber (1838-1924) was the first to volunteer. He joined the 20th Indiana Infantry Regiment, Company A, organized in Lafayette in July 1861. They were then sent to Camp Morton in Indianapolis, named for Governor Oliver Morton. It was previously used as the state fairgrounds and made an ideal site for a military training ground that had to be ready in weeks. It was about 36 acres, with buildings and horse stalls, “easily converted into a great barrack for the reception and accommodation of troops,” as noted in the Indiana State Sentinel. Cattle and horse stalls were fitted up to house six bunks each, “snug and cozy.”

The men received what little training they would get - a lot of drill and rifle practice - and were issued their uniforms, guns and other equipment. The uniform was a gray jeans suit with a Zoave jacket with braided trim of black velvet. The men were disappointed to get older-model guns rather than the new ones they anticipated. They were promised new ones as soon as they could be procured.

The regiment was transferred to Baltimore by train, then sent by steam ship to Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia. Next they were sent to Fort Hatteras in North Carolina, recently taken by Union forces. In a letter home that was published in the Plymouth, Indiana Weekly Republican, a private named Henry Quigley wrote that Hattaras Island was so filled with grapes and such an abundance of oysters and fish along its shores that they stopped eating their rations.

For most men it was their first time away from home, and away from about a 60 mile radius of home. Seeing the ocean and collecting oysters must have been a wonder to Myron.

In November, equipped with promised new guns, they were transferred back to Fort Monroe where they witnessed the Battle of Hampton Roads, also known as the Battle of the Ironclads. After fighting in the Battle of Seven Pines, the regiment was transferred to the Army of the Potomac.

Myron and his regiment fought in many battles, including Gettysburg. He served for three years and was wounded in battle. It would be fascinating to have his personal details.

Calvin Sutton Barber (1843-1930) and Milo Roswell, Jr. (1842-1917) were next to join. Both brothers joined the 26th Indiana Infantry Company A, organized in Indianapolis, on August 1st. Milo entered with a rank of sergeant. They too trained at Camp Morton. Their regiment was sent to St. Louis, and with other regiments, was organized as the “Army of the West,” becoming part of the Western Campaign.

In October 1861, Miranda Barber was surely worrying about her three soldier sons. Quartermaster General of the United States M.C. Meigs issued an appeal to the folks on the home front for wool blankets. As winter approached, there were not enough to meet the need for all the troops, nor any to be had for money as mills strained to meet demand, and the Army waited for a shipment from overseas. Families were asked to donate any surplus, and the editor of the Indiana State Sentinel pressed his readers to comply.

The Fort Wayne Daily Times praised “a widow in this city,” who gave her only two blankets to the soldiers at Camp Allen, Fort Wayne’s training ground.

Milo was honorably discharged in June 1862 in Jefferson, Missouri with disability. He may have been injured in one of the many skirmishes the regiment engaged in during their pursuit of General John Marmaduke’s Confederates, which resulted in the loss of many men. He headed home to Silver Lake to recover.

Calvin of course continued serving, and with the 26th was part of the Siege of Vicksburg. This was a battle for control of the Mississippi River. Jefferson Davis said Vicksburg was the “nailhead that holds the South’s two halves together,” and Lincoln said the war could never be won without victory in Vicksburg. After a 47-day siege, a staggering 37,000 men died, 4,900 from the Union Army. Food shortages were such that Vicksburg residents were killing cats and mules to eat. But the Union prevailed.

Calvin and the other men didn’t get a pat on the shoulder and a ticket home, of course. For them, it was on to the next battle, the Battle of Brownsville (Texas). This was a successful effort to stop Confederate blockade runners along the Gulf Coast in Texas.

Calvin was honorably discharged in 1864.

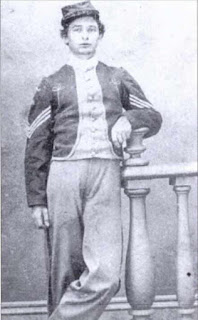

Sylvester's cousin, Lucius Taylor Barbour, in the uniform of the 12th Indiana Infantry

Sylvester Barber (1846-1905) and his cousin Lucius Taylor Barbour volunteered for the 12th Indiana Infantry, Company F in Sylvester’s case, and Company K for Lucius. The regiment was organized in Indianapolis, Sylvester joining June 20, 1862. After training the regiment was sent to Kentucky where they joined a division of the Kentucky Army. Within days, they were some of the “haughty minions of Northern despotism,” as a Macon, Georgia newspaper said, who were fighting in the Battle of Richmond (Kentucky). After three “severe engagements,” in twelve hours, they were trounced. It was one of the most complete Confederate victories of the war; the Indianapolis Star called it “the disastrous engagement.” Sylvester and Lucius were two of the 2,000 to 3,000 prisoners captured (estimates vary) along with their artillery, small arms, wagons, stores and other equipment. They were held until a November prisoner exchange, paroled and sent to Indianapolis.

Soon they were returned to service, Sylvester taking part in the Siege of Vicksburg before being sent to Nashville where he remained until discharge. A biographical account later in his life said, “The privations and hardships he experienced so reduced him in flesh that when he returned from Nashville his weight was only 85 pounds.”

“War! War! War! Citizens of Johnson Co.: Your country, struggling with Treason, calls aloud to you to help,” blared an ad in an Iowa newspaper. Abraham Lincoln had recently put out a call for 300,000 volunteers in July 1862. A mass rally was held in early August in Iowa City, Iowa.

Charles I. Barber (1833-1901), responded. The oldest son, he left home before the Civil War and was living in Shellsburg, Iowa, 23 miles from Cedar Rapids. Shellsburg was such a new town that it gained a post office only in 1859 and was still not connected by railroad. Charles joined the 28th Iowa Infantry Company A, which was organized in Iowa City, in August 1862. The enthusiasm at the rally, and possibly threat of draft, was said to motivate many men, and more than twice Iowa’s quota was met at this time. He was the only one of his brothers to leave a wife behind.

Charles was trained at Camp Pope, which also came into existence that August. After two months of drilling, they marched through Missouri to an encampment in Helena, Arkansas, arriving November 20th. After participating in the Siege of Vicksburg, he was discharged on disability. Charles returned to his parents’ home at Silver Lake.

The sixth son to serve was George M. Barber (1849-1869). The other sons, Edwin and Theron, who were born in 1851 and 1857, were too young to join the war effort. The same could be said for George, and how, precisely, he was allowed to join at 15 is lost to time. The recruitment age was 18. About 200,000 underaged boys served, about 10 percent of the Union Army. It could have been a matter of the pressure to meet recruitment quotas, being able to pass for 18, or knowing someone who knew someone who vouched for him. George joined the 128th Indiana Infantry, Company G, organized in Michigan City, in March 1864. Almost immediately they were sent to Nashville, then marched to Charleston, Tennessee, a distance of 174 miles. That in itself must have been a tough introduction to military life for a 15-year old.

George’s regiment was part of the Atlanta Campaign. Atlanta, of course, was a major manufacturing center and railroad hub for the South. Nearly 70,000 men died in the Union’s attempt to take the city, and the Confederate’s attempt to hold it. The Union victory after four months set the stage for Sherman’s famed March to the Sea.

Following this, young George was sent to North Carolina where his regiment participated in the Carolinas Campaign. This was the last campaign by the Union Army against the Confederates in the Western Theater. They were at Joseph Johnston’s surrender at Bennett Place, North Carolina, and served the rest of their time in the state in locations such as Goldsboro and Raleigh. He was honorably discharged in April 1866.

Re-Enlistment

After recovery from disability, Sylvester and Milo Jr. both reenlisted. An interesting study found that farm laborers re-enlisted at higher rates than more skilled and white collar workers. It seems like common sense. Re-enlistment bonuses could equal several years of wages on the farm; this could be enough to purchase their own land. Serving as a soldier was steady work when increasing farm mechanization eliminated the need for as many “hands.”

Sylvester returned home from his first enlistment weighing 85 pounds, but as soon as he recovered, he joined the battle again. Milo did the same, evidently recovering sufficiently from disability to serve in the 118th Indiana Infantry, Company G from August 1863 to March 1864.

The brothers enlisted together in the 138th Indiana Infantry, Company E from May 1864 until September 1864, when the terms of service expired. They were assigned to railroad guard duty in Tennessee and Alabama.

Milo finally completed his service in the 152nd Indiana Infantry, Company D. In this regiment, he served from February 18, 1865 to August 30, 1865, when their services were no longer needed.

Sylvester completed his service with the 26th Indiana Infantry Company A, which he joined November 30, 1864 and was mustered out November 29, 1865. Sylvester was discharged as a corporal.

All the “Barber Boys” survived the war. What was next?

Nebraska

The Homestead Act, which had such a profound effect on the country, went into effect while the Barber boys were busy at war, January 1, 1863. A man or a single woman could claim 160 acres of land by living on the property for five years, building a home and raising crops. What could they do in Indiana? Their father’s farm wouldn’t support six additional families as the “boys” married and had children of their own. The Hoosier lands were already bought up, and acquiring an established farm would take money.

“Homesteads For Soldiers,” read the headline in November 1870 in the Waterloo Press of Dekalb County, Indiana. “We publish below the law giving to soldiers homesteads in alternate reserved sections of public land along our Western Railroads.”

In the Richmond [Indiana] Weekly Palladium in August 1870, there was an ad published by self-appointed “emigration commissioner” Daniel Scott. “The country is being populated, and towns and cities are being built, and fortunes made almost beyond belief,” his ad copy read. “Every man who takes a homestead will have a railroad market at his own door. And any enterprising young man with a small capital can establish himself in a permanent and paying business, if he selects the right location and right branch of trade.” For just one dollar, Scott could help that young man out with his advice. That was close to sending in $25 today.

Why the Barber brothers Myron, Milo, and Sylvester specifically chose Stromsburg, Polk County, Nebraska in 1871 is forgotten now. Calvin went to Saunders County with cousins. But there were many enticements to heading west such as the ad and articles if one wanted to farm. Then too, perhaps there were some dreams of wealth.

Calvin was the first brother to go to Nebraska. After the war, he went “back home” to Kosciusko County, Indiana, where he married Hannah Danser in 1868. They were enumerated in the 1870 census in Saunders County, Nebraska, and homesteaded near Valparaiso. Also settling in Valparaiso was the family of his cousin, Chauncy Hurlburt. Chauncy was the son of Rhoda Barber and Gurdon Hurlburt. Rhoda’s sister was Betsey Barber, who was Calvin’s grandmother (Milo’s mother). Living on the farm right next-door was Edward D. Hurlburt, Chauncy’s son.

Later they moved to Newport in Rock County, and in 1902 to Auburn, raising seven children.

Calvin’s wife died in 1917, and in 1918 he decided to join his daughter Mattie in California. Mattie was a teacher in her early adulthood in Nebraska, but switched to nursing. She never married, and Calvin made his home with her for the rest of his life, returning to Nebraska and Indiana each year to visit friends and family.

Calvin remained very active in the G.A.R. - the Grand Army of the Republic, a Civil War veteran’s group, to the end of his days. He also traveled each year to the group’s national “encampment” - their convention. In 1930, that was in Cincinnati. It’s hard to convey how important the G.A.R. once was, and how ubiquitous it was in the fabric of society for decades. Calvin was one of 12 members attending from California, “a long trip for men of their ages,” and at 87, marched in a parade seen by an estimated 225,000. That was something his father would have been proud to crow about.

Calvin was ready to return to Los Angeles when he learned of the death of an old Civil War friend in Nebraska, and decided to stay for his funeral. Then he went to Stromsburg to visit family. He accidentally fell down a flight of stairs, which led to his death. He was buried in Nebraska where he’d spent nearly 50 years of his life. The Auburn American Legion post handled his funeral, with three volleys fired, taps played.

Myron didn’t get rich in Nebraska, but found wealth in a family of his own, nine children with his wife Maggie, and a middle-class life. He and Maggie started their marriage in 1872 in a dugout on the south bank of the Blue River. They proved up their claim in five years, and continued to do well enough to send their children on to high school, when that was for the lucky few. Several of their kids attended at least a session with colleges like North Western Normal and Business College in Beatrice, Nebraska.

An example is his daughter Grace. When she graduated from Stromsburg High School in 1912, there were only 13 students in her class. She performed a duet at graduation, which was held in the Stromsburg opera house, with her older sisters Dot on piano and Madge on violin. After high school, Grace attended North Western College in Beatrice, living with her brother Lester and his wife. Madge taught violin lessons, driving herself in horse and buggy to students’ homes.

Milo Jr. returned home to Silver Lake, and in 1865 he married Mary Swalley. They chose to settle in Pleasant Home Township in Polk County. He and Mary had seven children; three of their sons would later serve as police officers in Portland, Oregon. In 1893, he was part of the land rush into the Cherokee Strip in Oklahoma, and one of the first settlers of Ponca City, Oklahoma.

Mary died in 1895 leaving him with three daughters still at home, the youngest 10. After five years raising his children alone, he remarried to Caroline Gates in 1900.

Milo spent the last two months of his life receiving care at the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in Leavenworth, Kansas, commonly known as the Old Soldiers’ Home. The homes were a precursor to Veterans Administration hospitals.

Milo Roswell Barber, Jr. in his later years

Sylvester spent the shortest time in Nebraska. After his return from the Civil War, he married Clarissa Stevens in Kosciusko County. The two moved to Polk County to homestead, but after 18 months they returned home. He was the son that would stay on the home farm, taking over management from Milo. Clarissa died in 1878 leaving Sylvester with three children who were only one, three and five years old. He remarried three years later to Minerva Callahan. In shades of his father, he was elected township trustee in Seward Township.

Those Who Stayed Behind

Then there was the other half of the Barber brothers, those who did not go to Nebraska. Charles, the oldest, was the only one who married before the Civil War. He married Barbara Hoover in 1857 and tried life out-of-state as a young couple, living in Shellsburg, Iowa. After the war they came home to Kosciusko County and stayed. Charles and Barbara were childless for twenty years when they had a daughter Florence Edith. She may have been adopted.

George packed a lot into his brief 20 years. After his service in the war, he married Selena “Lena” Miller in the fall of 1868. Just weeks later he was killed in a fight at the Silver Lake schoolhouse. (See my blog post “Death At the Spelling Bee” for details.)

Angeline and Edwin S. Barber with their first five children

Edwin Seward Barber (1851-1919) also had a tragic death, but his was agonizingly prolonged. April 30, 1892, a group assembled in Bourbon, Indiana for an inquest. Attendees included prominent local attorney and justice of the peace Rollo B. Oglesbee, who would soon serve as secretary of the Indiana State Senate; local physician Dr. Luther Johnson; Muncie physician Dr. J.S. Martin and four local residents.

Edwin wasn’t “right in the head;” he hadn’t been for awhile. The men assembled to determine whether to rule Edwin insane and get him committed to a mental hospital.

According to a biographical sketch in a local history, Edwin lived an adventurous life as a young man before coming back home to Indiana. At 20 he was in business as a fur dealer “having previous to that time worked at various occupations in different parts of the country,” traveling extensively throughout the “western states and territories,” returning from California in 1873. In 1877 he married Angeline “Angie” Bailey. They settled on a farm, and at the 1890 publishing date of the local history, he owned 136 acres.

Edwin’s eventual diagnosis, as listed on his death certificate, was “general paresis,” also known as “syphilitic paresis.” It is caused by late-stage syphilis. Had Edwin been living in a post-penicillin world, he could have been spared the tremendous suffering he experienced for decades, and the anguish and distress his family felt. The symptoms of the disease appear 10 to 30 years after infection. They are progressive, with personality changes and mental decline. Grandiose delusions, maniacal behavior, loss of social inhibitions and asocial behavior are common manifestations.

By the 1880s the link between this form of insanity and syphilis was known. But as a result, its victims found the opposite of sympathy. “It need have no terrors for anyone who does not invite it by its actions,” the medical superintendent at New York’s Randalls Island wrote in 1892, the same year as Edwin’s inquest. “...he is reaping what he has sown…” The illness was the result of immorality, and therefore, a choice easily prevented, the doctor said. Such were the times that the doctor said propriety prevented him from discussing the cause.

Those with general paresis made up about quarter of the population at insane asylums in Edwin’s day. But his case, if accurately diagnosed, must have been unusual as most victims died within one to five years of the onset of symptoms. Edwin lived 27 years after the first inquest into his sanity. He was finally admitted to the Northern Indiana Hospital for the Insane in 1899, leaving his poor wife with five children still at home ranging from a 17-year old to a one-year old. In 1919, Edwin fell and fractured a hip. This led to a pulmonary embolism, finally freeing him from years of suffering.

Someone has to be the “baby of the family” and in Theron L. Barber’s (1857-1916) case, it was him. The two oldest children, Abi and Charles, were already married when he was born. His first niece arrived when he was six months old.

Like Edwin, Theron was born too late to be part of his brothers’ grand adventures in the Union Army. He could have chosen to be a homesteader, but he did not. He married Anna Mariah “Annie” Harrold in April 1881. They had nine children, their first in May 1881, and farmed in Seward Township, Kosciusko County.

It is hard to find anything about him; he seemed to elude the newspapers. When he was enumerated on the 1910 census, he was still farming and owned his farm mortgage-free.

In 1916 he spent hours outside clearing weeds off of a property in a hot late-June sun. He came inside and drank some cold buttermilk, collapsed and died. At the time, the family blamed the buttermilk, but his death certificate listed an aneurysm as the cause of death.

Note: It was a “smaller world” in the past, when people often did marry “the girl next door.” And a sibling or cousin might marry her sibling, too. Crisscrossing in the family tree, Charles Barber married Barbara Hoover. Barbara’s youngest brother Peter would marry Alice Hatfield. Peter and Alice divorced after having three children together, and Alice married Lucius Taylor Barbour, Charles Barber’ cousin.

Milo Roswell Barber was the brother of my third great-grandfather, Myron Fitch Barbour.

Sources:

Clark, Frances M. and Rebecca Jo Plant. “Why the Union Army Had So Many Boy Soldiers,” Smithsonian Magazine, 17 Jan 2023. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/why-the-union-army-had-so-many-boy-soldiers-180981458/

History of Indiana : containing a history of Indiana and biographical sketches of governors and other leading men. Also a statement of the growth and prosperity of Marshall County, together with a personal and family history of many of its citizens. Publisher Madison, Wisc. : Brant, Fuller, 1890. [See p. 297 for brief sketch on Edwin S. Barber.]

“Record of the Insane, Marshall County, Indiana,” From: Marshall County Roots and Branches, Vol. 12, No. 1, January 1991, Judy McCollough, Editor and Compiler

https://sites.rootsweb.com/~inmarsha/recins.html

Robertson, John. “Re-Enlistment Patterns of Civil War Soldiers,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 32 No. 1 (Summer 2001), pp. 15-35.

The Thomas Barber Genealogy, Formerly, The Connecticut Barbers, Genealogy of the Descendants of Thomas Barber of Windsor, Conn. https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~barberfamily/genealogy/tbook%20part%2011,%20fam%20601-653.pdf

Williams, Henry Smith, M.D. “Wages of Sin: General Paresis of the Insane,” The North American Review, Vol. 155 No. 433, (Dec. 1892), pp. 744-753.

Newspapers:

“Camp Morton,”The Indiana State Sentinel (Indianapolis), 1 May 1861, p. 4.

“Indiana Military Items,” The Weekly Republican (Plymouth, Indiana), 8 Aug 1861, p. 2.

Widow with blankets: Dawson’s Fort Wayne Daily Times, 25 Oct 1861, p. 3.

Oysters and Grapes: “Military Items,” The Weekly Republican (Plymouth, Indiana), 17 Oct 1861, p. 2.

Copyright Andrea Auclair © 2023

Comments

Post a Comment