Going to Coffeyville: The Barbour Brothers' Second Chance

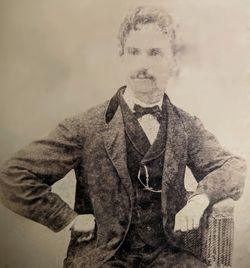

A young Myron Cassius Barbour

One set of my great-great-grandparents, Enos and Avarilla Patchett, homesteaded in Kansas in 1869. But another pair, Myron C. and Agnes Barbour, moved there in the summer of 1887. The difference in years meant they had totally different experiences. Enos and Avarilla traveled by wagon. Myron and Agnes came on the train. Enos and Avarilla arrived at a place where the town of Coffeyville didn’t yet exist. It was only a trading post, selling buffalo meat amid survival essentials. The prairie sod was unbroken, and the Osage were still living on their lands.

Myron and Agnes came to a growing little town of about 1,000 with a hotel, fraternal organizations, churches, schools with a total of 520 kids in attendance, stores and a photography studio. Fourteen freight and passenger trains steamed into the city each day. The Osage had long ago been pressured into moving to “Indian Territory,” and Coffeyville had the nickname the Gate City, because it was the gateway to that storied place.

There were other differences in the experiences of the two couples, too. The Patchetts both grew up on farms in rural, backwater communities in Illinois, where trains didn’t arrive until well into the 1870s. The Barbours had grown up in towns, Myron in the industrialized manufacturing center of Fort Wayne, where trains connected the town in the early 1850s. They did not grow up on the land; their fathers had white-collar occupations. Agnes’ father was a postmaster and doctor; Myron’s was a real estate dealer.

Enos and Avarilla lived lives essentially like people a hundred years before them. Myron and Agnes came from what could be considered the new America - urbanized and industrialized, with schooling beyond a few years in a one-room schoolhouse, to extend even to college.

So why did Myron and Agnes, and Myron’s brother Lucius, decide in midlife to leave their hometown and suddenly become farmers? Why did they settle on farms just outside Coffeyville in Montgomery County, Kansas?

Problems Back Home

I believe Lucius’ and Myron’s father had high expectations for his sons. Myron Sr. harbored college dreams for himself that went unrealized. Myron C., unfortunately, was kicked out of the Fort Wayne public schools as a young teen due to misbehavior. The school board made his return conditional on a guarantee from his parents that he would not misbehave again. I think his schooling ended then. Lucius was sent on to private academies and eventually, Antioch College in Ohio, where he was taking preparatory classes when the Civil War closed the college.

Myron Sr. tried setting his sons up in professions. He started Myron C. out as a dentist, working out of their home. He hired Lucius as a lightning rod salesman when he returned from serving in the Union Army. After he married he set him up as a pharmacist in his own store. Nothing lasted long.

Myron C. had a short-lived marriage followed by divorce, when there was great stigma to the latter. Lucius suffered from drinking problems that were no doubt a result of post-traumatic stress as a result of the battles he fought and nine months in Confederate prisoner of war camps. His wife left him and took their three children back to her hometown in southern Indiana. Lucius began living with Alice, a young mother who may not have been divorced from her husband yet. Meanwhile, Myron C. remarried to Agnes, had his only child, Clyde, and banged around working at various different things, including some position in a carpet sweeper factory.

In March 1884 Alice had a baby, Edna Naomi. Lucius was still married to Lizzie. A few months later, Lucius and Alice moved to Sterling, Kansas. The move may have been a way to get away from gossip; no one in Kansas would know that they weren’t married and that Edna was born out of wedlock, which was quite scandalous then.

Connections

In 1870 when the lands in Montgomery County, Kansas first opened for sale, William Edsall left Fort Wayne and established a farm in Fawn Creek Township. His brother Peter later joined him. Their father Simon moved there in 1881 or ‘82, although in 1883 he was back in Fort Wayne.

Lucius and Myron C. had known the Edsalls all their lives. Myron Sr. had known Simon Edsall since 1835 when he first arrived in Fort Wayne. Lucius, Peter and William were classmates together at the Fort Wayne Collegiate Institute. In 1855 they were all part of the second-year preparatory class, three of 65 students. The Institute was part of the Fort Wayne Female College; in fact, after that year the two would merge and be called Fort Wayne College. Myron Sr.'s brother-in-law, Richard Adams, served on the Board of Trustees for the female college, and Peter and William's uncle, Samuel Edsall was vice-president of the board. (In 1855 Samuel also served as a state senator.)

Their families had several parallel stories. Peter and William's father, Simon Edsall, born in 1809, had come to Fort Wayne from New York as a child. Myron Sr., born 1811, came from New York to Fort Wayne as a young man. Simon’s brother William worked for the Wabash and Erie Canal Company as a surveyor and head of the U.S. Land Office; Myron F. worked as the agent of land sales for the company. Lucius was born in 1841; Simon’s son William in 1844. In 1861, William and Peter Edsall joined the 30th Indiana Infantry while in 1862 Lucius joined the 12th Indiana. Both the Barbours and the Edsalls were Presbyterians.

It’s mot surprising that old friends and lifelong acquaintances might influence where the Barbour brothers settled. Nor is it surprising that he Edsall brothers and the Barbour brothers socialized together in Kansas.

Just as immigrants settled in areas with others from their homeland, there were clusters of people from the same state settling close by. There were many Hoosiers among the Barbours and the Edsalls. Neighbors the Augustines, the Coons, the Ernests and the Seldomridges were from Indiana. Teachers Homer Overhiser, R.Y. Kennedy and Andy Curry were all Hoosiers, all of whom taught Barbours or Patchetts, a family the Barbours married into. There were so many former Indiana folks that a Hoosier Club was formed and held at least one big countywide picnic in Cherryvale in 1887.

It was not uncommon for “colonies” from one state to move en masse to another. This is not how my sets of great-great-grandparents came to Kansas, but it explains how some areas were filled with settlers from the same area. For example, a group of 800 Ohio families bought 8,000 acres of land in Anderson County, Kansas from a railroad company. Colonists would set rules such as temperance agreements, or avoid land speculators by requiring that land buyers lived on the land for at least a year or they forfeited their purchase.

A Farm Life

In 1887 Myron C. and Agnes, and Lucius and Alice, had moved to Montgomery County. Lucius finally got a divorce from Lizzie and married Alice. Both families started new lives as Kansas farmers, thanks to the largess of Myron Sr. He bought a farm in Fawn Creek Township for Lucius and one in Parker Township for Myron C. It was a real estate investment for him, and a chance for his sons to establish a new career. However, the farms were not gifts, nor did Myron Sr. set up an arrangement in which they could buy the farms from him. Myron was newly widowed and 76 years old in a time when people in their late fifties were described as “aged.” Lucius and Myron C. may have assumed they would one day inherit the land. The two worked hard to improve the farms and each built a new house on the land.

In 1891 Lucius and Myron C. were not pleased by their father’s remarriage to Margaret McNaughton, a woman one year younger than Lucius. The marriage would have disastrous consequences for the Barbour brothers’ families down the road.

Making the Most of Things

But for a time - a period of about ten years for Myron C., and to the end of Lucius' life in 1903, the countryside outside of Coffeyville was indeed a good move. They built new houses and developed their farms. Both were very active in Republican politics and were chosen as delegates to the county Republican convention multiple years. They held fundraisers for ministers, and Agnes started a Sunday school and was elected leader. Lucius was elected Fawn Creek Township trustee. They were praised in the newspaper. Their father stopped visiting after his marriage to the much-younger Margaret. But from afar especially things probably seemed good indeed, and Myron F. was probably pleased.

A Father's Will

Myron F. died in December 1900. In January, the Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette ran the following brief item:

The will of the late Myron F. Barbour has been filed for probate. He leaves his entire estate in trust to Judge R.S. Taylor, for the widow, Margaret Barbour. Provision is made for Mrs. Barbour’s sister, Marjory McNaughton. After the death of Mrs. Barbour the estate is to be divided among the children.

Most women had few good options to support themselves other than marriage. Margaret was 49 when she married 79-year old Myron, and her older sister came along as a “packaged deal.” It was Margaret’s first marriage, and her sister never married. They were Scottish immigrants who somehow eked out a living before Myron came along. By Margaret marrying, neither had to worry about making a living anymore. Myron had income-producing real estate, and his house was probably paid off. The will stipulated that the trustee of the estate, R.S. Taylor, could sell off any property as needed for the support of the two sisters.

After Margaret’s death the will was to be divided amongst Myron Sr.’s children, but he did not divide it equally. He cut his daughter Eliza out of the will completely, saying that he had given her more help in her lifetime than all of his other children combined. He also cut his grandson Clyde out of the will, and he gave Myron C. a lesser amount than Lucius or their sister Sylvia. In addition, the three children Lucius had from his first marriage were ignored.

Off the Farm

Myron C.’s life as a farmer, enthusiastically praised by the Coffeyville newspaper’s editor, ended after about a decade. Lucius however, continued farming and raising race horses. His youngest children were only 7 and 10 years old when he died. His widow, Alice, attempted to keep the farm going for three years. But in 1908, the trustee of Myron Sr.’s estate, Robert S. Taylor, decided to sell the Kansas farms. Alice and Myron C. fought his actions in court. Myron was bitter about the improvements he had made on the farm. He asked for nearly $5,000 in compensation. Alice probably felt the same way about the 16 years her husband labored to improve their farm. In the end, they lost. The will was valid; they’d never owned the farms, and no arrangement had ever been made to pay them for improvements. Alice opened a boarding house in Dearing to support herself and sons Jesse and McKinley. Myron had tried a number of ways to make a living since he left farming, including running a railroad-stop restaurant. He would continue to struggle.

In the end, Margaret outlived all but Sylvia. She continued to live in Fort Wayne until her death in 1922 but she and her sister Margery took annual trips to Canada. I don’t know how much was left of the estate after 22 years, but Sylvia was the only one of Myron Sr.’s children still surviving.

Sources:

Catalogue and Register of the Fort Wayne Female College and the Fort Wayne Collegiate Institute For the Year Ending April 25, 1855, Cincinnati: Methodist Book Concern, 1855.

Suspended from school: Cook, Ernest W. "History of the Fort Wayne Schools For 100 Years," Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, 16 Oct 1921, p. 3A.

Marriage to Alice: 14 October 1887, Independence, Kansas, Film Number 001404632. Ancestry.com. Kansas, U.S. County Marriage Records, 1811-1911 [database on-line], Lehi, Utah, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc. 2016.

Will of Myron Fitch Barbour: Allen County, Indiana, Index to Wills, 1824-1899; Inventory, 1900-1920; Author: Indiana Circuit Court (Allen County); Probate Place:Allen County, Indiana.

"Publication Notice. In the District Court of Montgomery County, Kansas," The Daily Free Press and Times (Independence, Kansas), 7 Feb 1908, p. 7.

Comments

Post a Comment