The Woolcomber

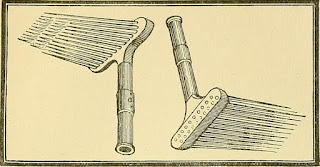

A set of combs used to process wool

William was my fourth great-grandfather, and Enos, age two at the time, was my third great-grandfather. William was a woolcomber, a trade essential to fabric production, but one that was extremely unhealthy and soon to be obsolete.

Before wool can be spun into thread, the fibers have to be untangled and straightened out, all facing the same direction. This was accomplished with a set of combs that were heated on small charcoal or coke stoves. The stoves were kept heated night and day to maintain the right temperature for the combs. The constant presence of the burning charcoal stove in the woolcomber’s house created dangerously unhealthy conditions.

Because combing was difficult to mechanize, it persisted as a cottage industry long after other textile jobs ceased to be. A machine was invented in the 1820s but did not work well. It wasn’t until 1850 that improvements were made to the extent that men could be replaced. Within a decade being a woolcomber was no longer an occupation.

However, that wasn’t the only part of the trade that made it a good one for William to abandon in 1846. In 1842, attorney and civil servant Edwin Chadwick published “Sanitary Condition of the Laboring Classes,” a damning report on the conditions of the poor that used the innovation of statistical information rather than just descriptive. It highlighted life expectancy based on occupation and residence. Whereas the wealthy in Bradford had a life expectancy of 39, the woolcomber’s was shockingly low, at only 16. Only about half of woolcomber’s children survived to age five.

An 1845 report by government official James Smith described the Bradford woolcombers encountered outside their home: “dung heaps …and open privies are seen in many directions…The main sewerage goes into the brook or canal. The water is so often charged with decaying matter that in hot weather bubbles of sulpherated hydrogen are continually rising to the surface….the stench is very strong…I am obliged to pronounce it to be the most filthy town I visited.” Smoke also blanketed the town from the many smokestacks. In 1840 Bradford had 67 steam powered textile mills. As the British National Library of Medicine said of this time period, “British cities had, it seemed under the aegis of economic transition, metamorphosed into epidemiological time bombs, environments greatly lacking in humanity and justice, particularly for the poor.”

There was still more working against the woolcomber. An 1845 news article covered a meeting of the Woolcombers Protective Society at Oddfellows Hall in Bradford and said, “no class in the community required more public sympathy than the woolcombers of Bradford.” They were placed “outside the pale of society” - landlords wouldn’t rent to them; they were shut out of decent houses and forced to rent filthy ones. As soon as landlords heard a man was a comber, he was refused. Woolcomber George Wilson said where he lived there were no less than five privies in a yard 18 ft long “beside ash heeps, swill tubs, and other offensive matters, which sent forth such a stench as to materially affect some better class property behind. He and his wife traveled scores of miles seeking housing but could not find it because he was a comber.”

The article said they were treated like dogs or pigs, that even in a tavern other textile workers would draw away from them. Since the Chadwick report they were known to be “the most unhealthy men in England and the majority of deaths occurred among their children.”

The woolcombers wanted shops built so they were not working in a house where the bed was often just feet away from the smoking charcoal stove. People feared that if they kept complaining “machinery would be got,” but leaders countered that while men were doing the work by hand, they should be treated as men.

The passage of the Poor Act in 1834 and 1837 was another concern. Prior to its passage, when the textile mills shut down for weeks due to low prices in the market, people could seek cash assistance or get help with food or fuel or blankets from local officials. They could keep their family together through rough times. The Poor Act was designed to be punitive and to discourage all but the most desperate and destitute from seeking help. It mandated that poorhouses be built, if they were not already in existence, and their intent was to be run like a prison. In the poorhouses, families were immediately separated. Everyone’s head was shaved and a uniform was issued. They received the most meager and monotonous of meals and worked all day at tasks like breaking rocks and picking oakum. (Oakum was the fibers of old ropes, laboriously untwisted and picked apart to make caulking for the wooden ships of the day. Picking it was tedious and created sores on people’s fingers.) The poor were blamed for their poverty and treated with contempt.

Residents of Bradford believed the laws to be cruel, unchristian and dictatorial. In 1837 an estimated 5,000 people rioted at the courthouse. Cavalry troops with sabres and muskets were sent to quell a mob armed with stones. But of course the law was not changed.

More current to the time of William’s departure was the Irish potato famine and the droves of Irish, most illiterate and many unable to speak English, who flooded into Bradford seeking any work.

The Journey

There are so many unanswerable questions today about the Patchett family immigration. How did William come up with the money to pay for passage of his entire family? Why did he pick Illinois? How did he decide on Clark County? Was there any connection – anyone he knew who had gone there before him? What did he do to provide for his family in their first year, and how were they housed? How does one go from being an urban woolcomber to a prairie farmer? What were his thoughts about this move and this new country?

There were 56 men on the Condor, eight of them woolcombers. There were a few others in the textile field, but a lot of shoemakers. There were 20 women, and 42 children under the age of 14. They sailed on March 17th. It was a sailing ship, and being a passenger on one was itself an ordeal. According to Enos’ obituary, they were scheduled to stop in Cuba, which was a common stopping point for fresh water and food. But a yellow fever epidemic prevented that stop, and the ship went on to its intended destination without fresh provisions. They landed in New Orleans, the land of dreams, on June 1, 1846 after ten weeks of travel.

They took a steamship up the Mississippi, another amazing trip that it would be wonderful to have the details. How long were they in the city before William was able to gain passage on the steamship? In 1831 an Englishwoman, Rebecca Burlend, immigrated from Leeds, West Yorkshire to Pike County, Illinois. In 1848 she would publish an account of their experiences. She noted that before immigrating, she had never been more than forty miles from home, which was probably true for the Patchetts. She described her impression of the city:

We reached New Orleans on Sunday morning; but when I came to survey the town more leisurely, I could scarcely believe it was the Lord’s day. I remembered that frequently on our passage I had heard it remarked that the time varied with the time in England a few hours, and for a moment I supposed that the Sabbath varied also.The reader will perceive the cause of my surprise, when he is told that the shops were everywhere open, stalls set out in all directions, and the streets thronged with lookers-on more in the manner of a fair than a Christian Sabbath. This I was told was the general method of spending that day in New Orleans. With regard to the inhabitants, their appearance was exceedingly peculiar, their complexions varying almost as much as their features; from the deep black of the flat-nosed negro to the sickly pale hue of the American shopman.

This city is a regular rendezvous for merchants and tradesmen of every kind, from all quarters of the globe. Slavery is here tolerated in its grossest forms. I observed several groups of slaves linked together in chains, and driven about the streets like oxen under the yoke. The river, which is of immense width, affords a sight not less unique than the city. No one, except eye-witnesses, can form an adequate idea of the number and variety of vessels there collected, and lining the river for miles in length. New Orleans being the provision market for the West Indies and some of the Southern States, its port is frequented not merely by foreign traders, but by thousands of small craft, often of the rudest construction, on which the settlers in the interior bring down the various produce of their climate and industry.

The Burlends hoped to leave immediately to head upriver, but no steamer was leaving till the next day. It took twelve days to travel from New Orleans to St. Louis. She described their “anxious suspense” throughout their long journey. From St. Louis they boarded a smaller and “greatly inferior” steamboat to get close to their final destination. She described the shock she and her husband felt when they were dropped off at Phillip’s Landing in Illinois. It was night and they could see no buildings or signs of life. They didn’t know how to proceed - where to go or what to do. Both she and her husband burst into tears, scaring their children. Then her husband set off through the woods in search of a cabin. When he found one, they were taken in for a few nights until they could locate “Mr. B,” the Englishman her husband corresponded with.

Illinois

Back in 1817, Morris Birkbeck, an English Quaker, was tired of paying taxes to a church he didn’t belong to or attend. He moved to Illinois and bought a vast swath of land to start an English Colony in Edwards County. In 1818 he wrote a best-selling book, Letter From Illinois, for the folks back home about his experiences, and extolling the superior living conditions of the prairie. It went through many printings, so maybe William had seen a copy. But more recently, in the 1840s there were dozens of letters published in English newspapers from Illinois immigrants and one from the state auditor of public accounts, William Ewing.

“Come to our country! Its government is mild and parental,” he wrote. “It is boundless in extent, the fertility of its soil incomparable.”

The letters from immigrants had an irresistible appeal to landless and hungry workers. All the letters told of the abundance and cheapness of food, and how one could hunt wild game without fear of being accused of poaching. One could make soap and candles without being taxed. Mary Harvey, writing from Kaskaskia, told her mother about the lack of class distinction, and how a poor girl could marry rich. She said, “A laborer’s son is as good as the governor’s son.”

An 1843 letter writer could have addressed William directly. “Do not be discouraged at the change of business; almost anybody can farm in this country,” he wrote, saying as little as 20 acres would produce all you need. “Here you may find a land of sweet employ and live your life in peace and joy!” He added that, “You won’t be compelled to support a constabulatory force nor the religion of state. Poor rates, magistrates’ rates and Church rates will sink into forgetfulness…you can choose what religion you like and pay what you like for it!”

Clark County

From the benefit of hindsight, looking at things in 2023, Clark County doesn’t seem like the most promising place for an immigrant to settle in. But then again, it depends on what one wanted. If one just wanted farmland with little interest in a big town with amenities including churches, schools and assembly halls, it might have been just right. Marshall, the county seat, was getting started only a decade before the Patchetts arrived.

Clark County borders Indiana with the Wabash River running between. Its county seat is twenty miles from Terre Haute. It was on the National Road, the nation’s first federally funded highway. Built between 1811 and 1837, the road was 620 miles long and began in Cumberland, Maryland. The 1880s history of the county said that it presented a good appearance in dry season, but became “in wet season, a very quagmire, through which horsemen were obliged to lead their floundering animals.” As late as 1845 local leader Judge Harlan would have a servant harness his horse on Sundays and take a wagon around town to pick up ladies for church. The wagon would go from the doorstep of the house to the threshold of the church. There were no sidewalks and it was the only way to get any kind of crowd, even during a revival.

The county seat, Marshall, according to the historian, had an “unprepossessing appearance.” For over 30 years it was “handicapped by competition with older and more successful towns, and a lack of public-spirited men.” Merchants had to transport their goods to Terre Haute or get them on a boat down the Wabash in the small community of Darwin. The railroad didn’t arrive in the county until 1868 or connect to Terre Haute until 1870. “All of Clark’s early railroad projects resulted in failure, and she was doomed to sit idly by, and see many of her sister counties, younger in years than herself, prospering through means of railroad communication of which she was wholly deprived,” according to the historian. Unsurprisingly, this “did much to limit growth and prosperity.” As late as the 1880s, after William’s death, cows and pigs were allowed to roam through the town. (Pigs had to have rings in their noses to prevent them from rooting around, however.)

Most early residents of the county had come from the South. There was sympathy towards the Southern Cause. The county voted Democratic until Teddy Roosevelt. During the Civil War a group of Copperheads were active in the county. Copperheads opposed the war and blamed it on abolitionists. They wanted Lincoln ousted from power, viewing him as a tyrant. They encouraged Union deserters. William’s son Thomas would choose to fight for the Confederacy during the Civil War, and would lose his life at Gettysburg.

Settling In

This was the place where the Patchetts settled. In August 1847, little more than a year after landing in New Orleans, William walked into the land office in Palestine, Illinois and bought forty acres of land in Clark County, paid in full, at the rate of $1.25 per acre. He would farm for the rest of his life - nearly thirty years. What did he do to earn money and keep his family afloat in those two years? Did he provide needed farm labor on someone else’s land? His older sons, Mathew, 19; Thomas, 18; and Hiram, 15, (their age upon their arrival), would be expected to do the work of men. They had to be essential to his success.

Joshua Garside, writing to an English newspaper in 1851, could have been telling William’s story. “Some follow farming who but a few years ago were cotton spinners, powerloom weavers, and dressers, and now most of them own pretty good farms of from 40 to 160 acres, and are doing very well.” It had been four years since Garside arrived in Illinois. “It is a very great change for a person to come from the cotton factory and to go on to a farm; the new kind of labour, the difference in food, mostly at first cornmeal, or what is more properly called “pork and corn dodger,” the entirely new mode of living, and the comparative loneliness which the transition from town to country brings upon, discourages many; and it is only by steady perseverance and a firm determination to overcome these difficulties that he can expect to succeed in his new undertaking.”

One thing Rebecca Burlend’s husband did was connect with a local man who immigrated a year before them. So when they arrived in Illinois, they were going to him for help. Maybe William was wise enough and fortunate enough to have such an arrangement. The Burlends also relied on the counsel of their distant neighbors in learning things such as how to make soap, which also involved learning how to make the necessary lye.

After Immigrating

No doubt William and his sons worked long and hard to acquire the money for the first forty acres William bought, and then to establish his farm. But tragedy hit the family when they were just beginning to get their bearings in this new country. Sarah died at the beginning of August and was buried in the Marshall Cemetery. She was only 42. Was it fever and ague? Malaria killed many, but there were so many ways to die then. A cold turned into pneumonia and in two days someone was gone. She made it to America. Sadly, she was not able to build a home there. Little Enos was only two.

In 1850, William was enumerated on the census in Marshall Township, Illinois on August 13th. Besides himself, his household consisted of Thomas, Mathew, Aaron, Mary Ann and Enos. Who is Aaron? Probably Hiram. Mistakes were made on the census, and Hiram and Aaron’s birthdate line up. All three sons were listed as farmers. Mary Ann, 14, probably had to be the “mother” of the house. Enos was nine. Did he go to school? Enos could read but curiously never learned to write.

In 1857, a major event happened in their family. William’s younger brother Thomas, with his wife Martha and children Mary, Matthew and Frederick, boarded a ship in Liverpool and sailed to New York. They traveled across their new country to Clark County, where they surely received a hearty welcome. The Patchett brothers came from a large family of eleven kids, and they were the only two who came to America.

Thomas was not working as a woolcomber. His occupation started with a ‘B’ but the rest is illegible. In 1845, the year before William immigrated there were an estimated 10,000 woolcombers, a staggering number. By 1854 that number was down to about 3,000. A newspaper article noted, “No doubt forethought and enterprise had led many to leave an occupation, the doom of which was written on its four fronts; some have casually been absorbed into other departments but there is to be remembered the frightful distress experienced in the town in 1846 and the ravages of cholera in 1848, to which a fearful amount of the decrease is to be attributed; for prior to those years, while the average age of death of the agricultural laborer and their families in the Bradford union was 32 ½ , the average age of death for woolcombers and their families in the same union was only 16 years, and it is absolutely certain that a class so decimated by disease under ordinary circumstances would furnish quite its proportion when famine or epidemic seized upon it.”

The best way to help the 3,000 remaining was still being debated. It was proposed that they should immigrate but here was no fund to pay for it. Colonial Emigration Commissioners turned them down. A Tazmanian newspaper said, “Woolcombers are not the people wanted in our colonies, not even as shepherds in Australia, to replace those who had hastily run off to the gold diggings, leaving their sheep in the wilderness.”

Three hundred were accepted at an agency for those willing to seek other occupations such as farm laborer; they had to meet qualifications such as age. Another 300 worked on a test hill at the poorhouse. In 1856 a Woolcomber Emigration Society tried to help, but as always there was a lack of funding. However Thomas managed to pay for his family’s trip to America, he had the great advantage of help from his brother.

Things weren’t any better in the old hometown in terms of a healthy environment, either. A report described it: “The canal, like a filthy open sewer, runs along the border of the town, breathing pestilence and death. There are yet the crowded dwellings - the death center of the town; the sewerage is still very imperfect, and the choking thick smoke of the factories pollute the air. The mortality of the borough is a very high one…”

In rural Illinois the air was clear and clean. But there was malaria, and before antibiotics people died of things that seem so minor to us today. Unfortunately, in 1860, Thomas’ wife Martha died (William’s sister-in-law) and was buried beside Sarah. After Martha’s death, Thomas moved to Vermillion County, which, in an interesting contrast to Clark County, was founded by Southerners opposed to slavery. Its residents were strongly supportive of Lincoln.

Transitions and Change

Evidence that William’s hard work paid off was in the 1860 Federal Census Non-Population Schedules. It recorded that William owned 360 acres of land, 100 developed, and that the worth of the farm was $5,000. This was substantially more than his neighbors. He owned three horses, two “milch” cows, six “working cows” (presumably oxen) and 25 swine. He had 235 bushels of wheat, 1,500 bushels of Indian corn and 40 bushels of oats. He had moved from Marshall Township to Douglas Township.

The 1860s were a time of upheaval and change for the country and the Patchett family personally. There was son Thomas’ death in 1863 at Gettysburg, where he served with the 1st Regiment, U.S. Army Artillery. That same year, Mathew finally married at age 34, to an Irish immigrant neighbor. After the birth of a son in 1864 whom he named after Thomas, his young wife died. He remarried to the sister of a neighbor in 1865, a widow named Eliza. Enos married in 1866 to Avarilla Stevens, a girl from Edgar County, just north of Clark County. Enos and Avarilla buried two baby daughters in the Baptist cemetery in Clarksville. Sometime before 1870, William finally remarried, to a Kentucky girl named Emaline, a widow. It’s uncertain what happened to Mary Ann, though she probably married. Hiram was the only child to stay close to home. He farmed right next door to his father.

In 1869, Matt and Eliza, and Enos and Avarilla left Clark County forever and went to Kansas to establish homesteads. William died in 1877. He was buried at the Clarksville Baptist Church Cemetery.

Sources:

Birkbeck, Morris. Letters From Illinois, London: Taylor and Hessey, 1818.

Burlend, Rebecca. A True Picture of Emigration, Chicago: Lakeside Press, 1936.

Flower, George. History of the English Settlement in Edwards County, Illinois, Chicago: Fergus Printing Company, 1882.

Foreman, Grant. “English Settlement in Illinois,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol 34, No. 3 (Sept. 1941), pp. 303-333.

James, John. The History of Bradford and Its Parish, London: Longmans, Green, Reader and Dyer, 1866.

Morley, Ian. “City Chaos, Contagion, Chadwick and Social Justice,” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, December 2007, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2140185/

“Morris Birkbeck: An Advocate for Illinois Settlement,” Illinois History and Lincoln Collections, 7 Dec. 2018, https://publish.illinois.edu/ihlc-blog/2018/12/07/morris-birkbeck-an-advocate-for-illinois-settlement/

Perrin, William Henry. History of Crawford and Clark Counties, Illinois, Chicago: O.L. Baskin & Co., 1883.

“Report to the Mayor of Bradford on the Operations of the Woolcombers’ Immigration Society,” 23 Oct 1857, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2675463530/view

“Stories in Stone - Timeline - Bradford’s Migratory History,” Historic England Education, https://historicengland.or.uk

Newspapers:

“Public Meeting of the Destitute and Unemployed Woolcombers of Bradford,” The Morning Post (London, England), 29 Dec 1846, p. 2.

“The Sanatory Movement,” The Bradford Observer (Bradford, West Yorkshire, England), 6 Nov 1845, p. 6.

“Annihilation of the Trade of Woolcombing at Bradford, in Yorkshire, The Courier (Hobart, Tasmania), 7 Sept 1854, p. 2.

“Death Calls Kansas Pioneer,” Nowata Daily Star (Nowata, Oklahoma), 27 Oct 1925, p. 6.

Copyright Andrea Auclair © 2023

Comments

Post a Comment